Thailand's air pollution: Aom's story

Madre Brava’s report Tackling the maize haze: how protein diversification can clean up Thailand’s air predicts that more than 300,000 people will die from respiratory diseases caused by smoke from maize burning if Thailand’s protein production continues at its current pace until 2050.

This is a shocking number. But the statistic does not tell the full story of the effect of protein production on Thailand’s air pollution, particularly the deadly smog which disproportionately hits the north of the country.

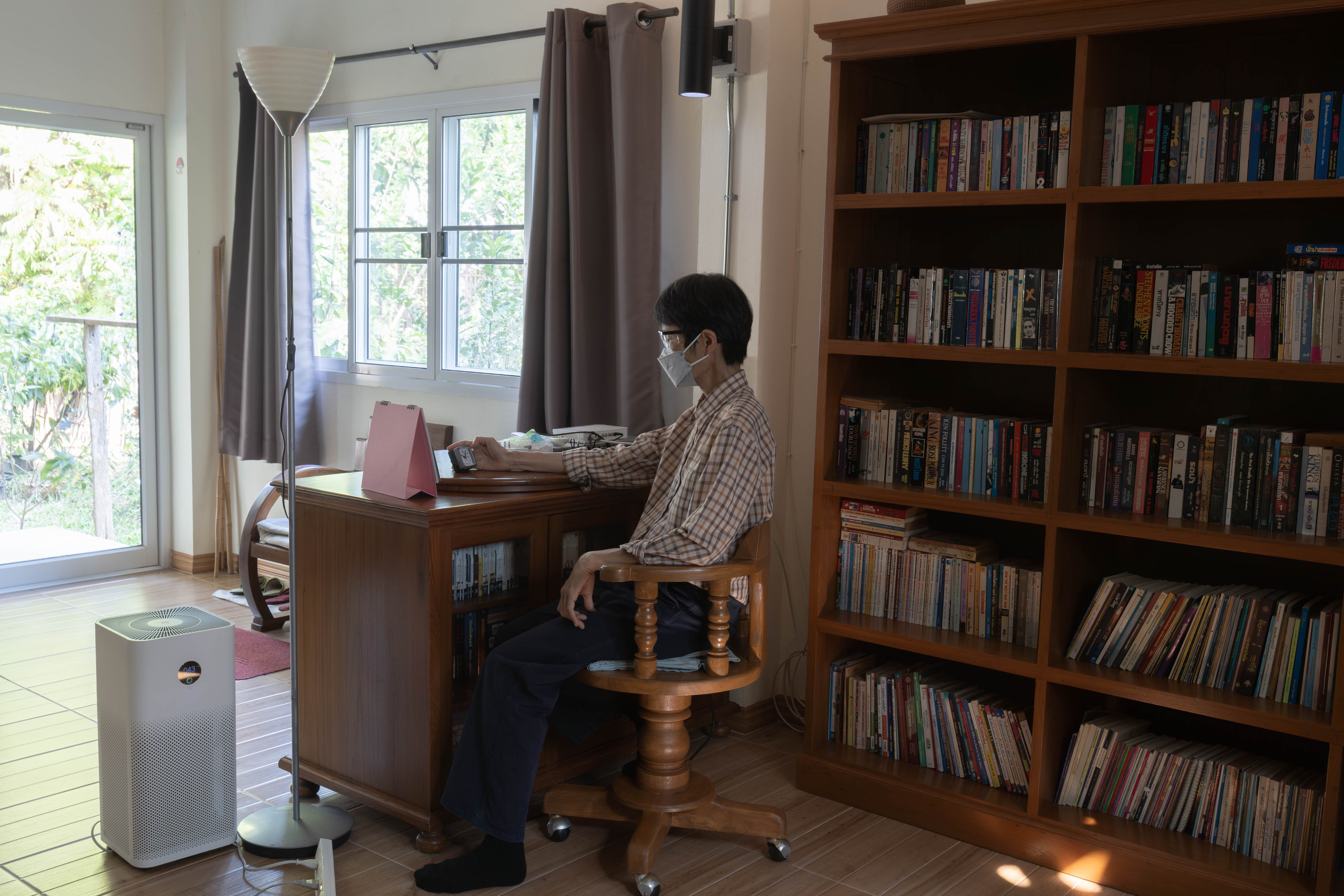

The human impact is very real. We asked Aom Wanaruk Saiphunkaew, a former lecturer in the Department of Biology at Chiang Mai University to share her personal experience of air pollution.

Below, she talks about its affects on her family, her colleagues and her own health.

I grew up in Udon Thani Province. When I first came to Chiang Mai in my third year of secondary school, I was amazed by the beauty of nature in Chiang Mai.

On both sides of the road from Lampang to Chiang Mai, there is a stream. I remember looking out at the clear stream and seeing the water flowing through the rocks. On the way back, I was compelled to look out again at the beautiful stream.

I became a biologist and moved to Chiang Mai in 1994 to become a lecturer in the city’s university.

An air pollution warning sign

One of the things that I studied was lichen, which is a kingdom of algae, yeast, and fungi that live on trees or rocks. These three groups of organisms live together and benefit from each other. They are sensitive to air pollution and have been used as a bioindicator to monitor the quality of air.

It was lichen which first alerted me to the air pollution. Around 2007, I noticed that many lichen in Chiang Mai turning white, which means they were dying. This was the first time in my life that I saw so many dead lichen.

The lichen was a warning sign that Chiang Mai was no longer the same.

In the same year, Chiang Mai had smog in the air in February. People started coughing or had sore eyes and noses. That was the year that I remember air pollution started to be reported in the news, but it still didn’t receive that much attention from the media.

Even though the pollution had improved within a month or two, it returned every year, some years are worse than the others, but it has the tendency to just get worse, and last longer.

And this wasn’t something that I could forget about between peaks in pollution. It is something that deeply affected my life: 11 years ago I lost my mom. And In the space of just three years my father and a fellow lecturer in the same subject as me died from respiratory diseases.

A family devastated by air pollution

My mother and father were not originally from Chiang Mai. They moved to Chiang Mai after my father retired from the Royal Forest Department in the Northeast. They wanted to be nearer to me.

In 2012, five years after I first noticed the lichen dying, my mother started coughing very hard. When she went for a check-up, doctors found numerous nodules spreading all over her lungs. After living with cancer for more than a year, and undergoing chemotherapy, she died in 2014.

Time goes by and life must continue. After everything returned to normal, on one fine day, I received a message from a junior lecturer in my department, Ajarn Phanuwan.

It said simply: “I have lung cancer”

I met Ajarn Phanuwan Chantawankun, or Ajarn Nu, at Chiang Mai University, Department of Biology. We lived in the same dorm, our rooms were next to each other.

We became close friends. Ajarn Nu was young, only in her 40s, with a promising career still ahead of her. She did not smoke or do anything else obvious that would raise her risk of cancer.

When I received that message, I was so shocked.

Her illness got worse and Ajarn Nu had to go to the Intensive Care Unit. I remember visiting her in the ICU. She couldn’t speak because she was on a ventilator. When I arrived, she opened her eyes. We held hands and I could feel her hand squeeze mine.

Ajarn Nu died in 2022, the same year that I lost my father.

My father’s symptoms were unclear at first. He started with a cough, but it wasn’t very bad. It was like an allergic reaction. When the symptoms first started, we didn’t think it was a respiratory disease.

But he started to get tired easily. He started to struggle to walk even short distances. One day, I measured his heart rate, and found that it was beating abnormally fast, at 120 beats per minute, so I took him to the hospital.

The doctor found three coronary arteries were blocked. He had a growth in his lungs, almost nine centimeters long, spreading to other organs, and he had emphysema, even though he had never smoked. He was in the hospital for just six nights before he died, not even long enough for an official diagnosis of lung cancer. There were no final words from him.

I then began to notice unusual health symptoms myself, like upper chest pain, bronchial hyperactivity, eye irritation, and seeing light streaks when looking at light.

I have quit my job to pursue what I enjoy doing because I don’t know how much time I will have left in my life. I have been going to temples to practice meditation and help with chores. And I am now considering moving away from the area.

An end to air pollution

The Thai government has acted, and introduced measures aimed at reducing air pollution, but Madre Brava’s report has highlighted another area where action which could be taken to help tackle the problem.

One can’t imagine what it feels like to arrange the funeral for three loved ones, all of whom had lung cancer, and to watch the smoke rise from their cremation – all in the same crematorium. You can’t truly understand, not until you’ve lived through it yourself. I was in unbearable pain and at one point, I even questioned why I should keep on living. But somehow, I made it through.

My hope is that we manage to reduce pollution as soon as possible, so others do not have to experience what I have.